Analysis

Avant-garde hard time

Its authors rather would strive collectively for an utopian social community in which they saw the sense of their actions. And that’s why we have some doubts about raising this issue in the magazine. However, if we look at the activity of say Stanis³aw Strzemiñski, a Polish avant-garde artist, we have to think about him as about a man of enterprise. This term however shouldn’t be understood, in the first place, as an ability to sell himself, but as professional activity, an ability to initiate culture events, and finally – as the power of persuasion which somehow made the outside world accept his ideas and artistic doings.

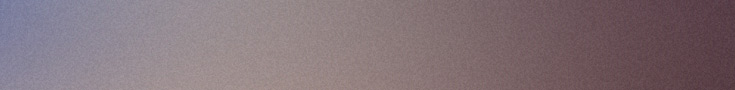

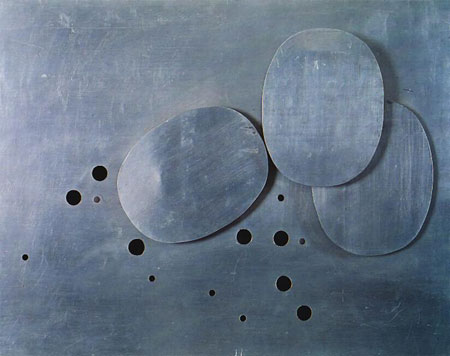

Katarzyna Kobro

Before we go further though, let’s define the field in which we would like to continue our divagations. The term avant-garde is very capacious and ambiguous. For the needs of this article we will limit its semantic field to a historic phenomenon which occurred in the interwar period. It seems right inasmuch as artists of the time can be straightforwardly perceived as the avant-garde. We can, of course, speak about the triumph of the avant-garde after the World War II, but this statement contains a logical error. If the avant-garde becomes the main stream, it ceases, by its nature, to be the avant-garde. And that’s why pre-war artists deserve to be called the avant-garde - at that time they constituted a “heroic” minority, seeking new ways, opening new spaces. We should however remember about some contradiction in the concept of avant-garde as such since its members tried to spread their ideas as widely as possible and believed that in the future their principles will indicate the culture to come. Thus, there is some internal crack in the fundamental understanding of the essence of being avant-garde; no wonder then that today this concept does not function as an organizing element any longer - rather than explaining the reality, it mythologizes it.

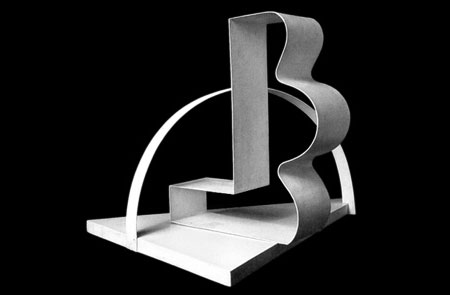

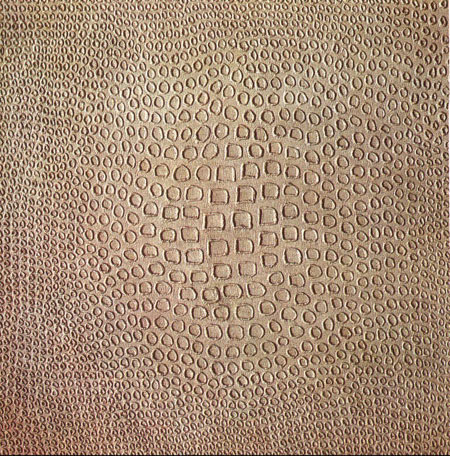

Kazimierz Malewicz

All that is the consequence of the manipulation of the word avant-garde itself. For some, this word has a positive character beforehand, it stands for innovation, expansion of borders, for new formal solutions. For others, it is a synonym of something subversive, that undermines tradition and is dangerous for the social binder. Therefore, it is very often marked with psychologism, which makes communication difficult. Defenders of the avant-garde, in their enthusiasm, see its positive elements only, disregarding all the negative ones. While the defenders of tradition negate the developments of the avant-garde, trying to ignore the changes it has brought. Let’s try to stand in the middle of this argument, quoting Marshal Berman’s opinion about modernism. I think that we can say the same about avant-garde. In his book All That is Solid Melts into the Air Berman says that the modernistic project, whose part the avant-garde was, has contained the element of evil since its very beginning. Modernism is not an innocent, positive kind of thinking that brings only social benefits, as the interwar avant-garde thought or wanted to think. Modernity carries some, and quite serious, costs that one should be aware of.

Piet Mondrian

Knowing that, let’s try to analyse briefly the actions of historic avant-garde. In Polish history of art this subject was extensively, although rather one-sidedly, described by Andrzej Turowski. He made a detailed analysis of the constructivist movement which he equated with what can be defined as the avant-garde of the first half of the 20th century. His fundamental works on Polish and Russian constructivism closely connected those movements with left-wing ideology derived from Marxists roots. But his earlier reflections about avant-garde, extremely enthusiastic, were slightly corrected by his later research (Avant-garde Margins, Builders of the World).

Henryk Stażewski

To quote Turowski: “The starting point of the avant-garde reflection of the 1920s was new anthropology, philosophy that redefined the place of man in the universe of his activities and products. Decadent feeling of isolation only raised suspicions in avant-garde artists. They did not treat seriously either the neo-romantic feeling of being different from nature or the alienation of man in the society. Art, “closed in an ivory tower”, was an aesthetic mystification, while liberated “I” and an individual rebellion against the world seemed an illusory delusion. The avant-garde of the 1920s, placing itself in a different perspective, wanted to see an artist as a subject and as a result of the transformation process of nature. Actively involved in history, an artist was expected to influence that process, creating a new world and himself. Artists defined the world in conformity with naturalistic and rationalistic tradition, i.e. a -, subordinated to the spirit of order - a dialectic whole of social, material and historic processes which involved people as well as objects. The universe and the avant-garde community developed constantly, were in continual progress, and the artist-builder – the worker of form, the engineer of ideas, in other words - the Creator and the main Organizer – participated actively in that construction. Avant-garde with its esprit nouveau, questioned, ultimately as it seems, the dualistic idea of aesthetic creation and alienated work. Creating the monistic vision of the world, the synthesis of spirit, it saw its goal, the goal of that world, in universal unity of art and production, of man and things.

Władysław Strzemiński

I used this extensive quotation purposefully because the language used by Turowski resembles the language (also artistic) used by avant-garde artists. This is a hermetic language, alien to colloquial communication and therefore limiting the possibility to reach wider audience. Also, being so “objectively” scientific, it is practically unquestionable and aspires to being the only language that binds. This seems to be the main source of the failure of modernism and avant-garde - the sin of arrogance which marked their main ideas, goals and first off all – their actions. Avant-garde artists, e.g. architects, thought that in the future the society will be structured as a splendidly working social machine. In the avant-garde vision of the world its fully conscious structure is the basis of all activities. It will be guarded not by some chaotic and unpredictable powers of the market, but by very well educated elites cooperating with the community for the common benefit. Those elites know much better than the public what its needs are. For instance, architects should be the only ones to solve housing and urban planning needs, and those who will live in their buildings and cities shouldn’t have any influence on that. The reason is education and specialisation which make architects more familiar with these disciplines. What was taken into consideration was neither an individual nor its needs, but the community which will peacefully adopt those ideas from the rational point of view.

How terribly wrong the avant-garde were, and that’s why they failed. Because they considered neither the diversity of the world nor, in the first place, its non-materialistic aspect. The failure of modernism is closely related to the materialistic and purely rationalistic vision of reality. No wonder then that, in spite of their efforts, they were doomed to failure. Today, the language created by the avant-garde is one of the languages we can use, but luckily - not the only one. Hard times have come for the avant-garde – it has to understand that it’s not the only, real, objective reality of culture. Whether it survives such difficult experience depends only on its surviving representatives. It seems very hard though. Because contemporary market is so skilful in converting everything to money that when the avant-garde sells its last non-commercial ideas, it will die with a natural if tragic death.

Check the archive

nr 25 October 2006

theme of the issue:

AVANT-GARDE

< spis treści

Article

From the Editors

Presentation

Janek Simon

Analysis

Avant-garde hard time - Artur Zaguła

Career in Culture

Souls agreement - interview with Agula i Tom Swoboda

Culture Industries

Avant-garde salary - Artur Zaguła

Workshop

To create and live - Maciej Mazerant

Young Culture

Something new - conversation with Jankiem Simonem

On the margin

Avant-garde - conversation with custodian Paweł Jarocki