Interview

Avant-garde artist or a storyteller

Works of Ilya Kabakov are about identity. Therefore, I would like to ask you: who is he really, as a man and an artist? Is he Ukrainian, Russian or maybe American?

Certainly he is not Ukrainian, we used to say he was a Soviet man because he was born in the time of the experiment which was called the Soviet Union. We can’t say he is Russian because Russia I have in mind has completely different mentality, culture and people. And because we were born and lived during that experiment, we can say we are the Soviets.

Indeed, he called himself a Soviet artist, but at one point he resigned from that. Why?

Because it is almost twenty years now since he left the Soviet Union. He can’t say that he is Russian because he doesn’t know what means to be Russian. We both have some kind of mixed identities. We are both Jewish, we were born in Ukraine, we left Ukraine for Moscow, we lived in Russia, most of the time in Moscow, he left in 1988 and I left in 1973. We live mainly - I wouldn’t say in America, I would rather say in the world of art. Somehow we managed to make a transformation and transferred ourselves from one world to another, from the Soviet Utopia to the utopia of art.

Is it good to live in such an utopian world? Is it better than the Soviet Utopia?

It’s fantastic. It is much better because in the Soviet Union, Kabakov never had an exhibition. He was an artist for thirty years and never had even one exhibition, and now in the world of art, fantastic, he has many exhibitions each year.

So now Kabakov can say he is an artist, not Ukrainian, not American, but an artist in the world of art.

Ilya Kabakov has always measured his work by art history and art, never by reality. Even if his installations are about reality, e.g. about the Soviet Union, they are not real. Art remains the same, reality is changing.

Now I would like to ask about the worlds of the East and the West. Is it difficult to be an Eastern artist in the Western society? Does he have to change as a man, an artist, as a member of the art market?

We are not a part of the art market, we practically discard what everybody thinks, we don’t have to work with others, and as you might have noticed, we don’t have auction prices. This probably makes our work more difficult, but I can’t complain, because we are lucky enough with museums and galleries. For an Eastern artist, for any artist who is going to another country; if you want to belong to the international art community and to the world of art, you have to remember one thing - that this world has its own universal language. If you don’t know this language, forget about being successful. In order to present yourself, you have to learn that language somehow. But you also have to preserve your identity as a person, as an artist. You have to be different from others.

Could you now describe the relations between Ilya Kabakov and the avant-garde art. He is a member of the conceptual movement which seems to be the last avant-garde current.

There are no such relations because conceptual art has nothing to do with avant-garde. I would rather say he is a contemporary artist. His dream has always been to belong to the world of art, to culture. He measures everything he does by the art history.

Are there any relations between him and the Russian avant-garde, Kazimierz Malewicz for instance?

No relations whatsoever.

Let me ask you about the works by Ilya Kabakov made after he left the Soviet Union. What kind of message do they carry ? Are they antitotalitarian?

At the beginning the message was as follows: an explorer comes to an island for the first time. He wants to be the first to explain everything to the inhabitants. So when he came to the West, he wanted to explain how much we suffered; the message was: look, that’s our life. People listen to the message, and then it fades. It isn’t in use anymore. It depends on your talent whether you can find another subject to make people interested. Kabakov found another subject. His message was: reality transformed through the fantasy of the artist. When he finished the project, the strategy ended, he came up with another fantasy, the fantasy of joker-words, characters, and many, many directions/others.

How important is the narrative side of his art?

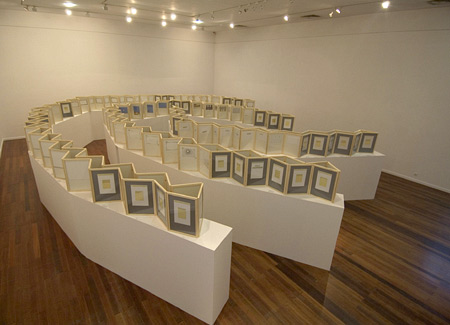

It is very important. In the 1970s. he started a specific genre, where he uses a narrative as a visual part of the art. So there were drawings and texts, it was done before, but never on such scale. When the installation is done, a viewer is moving through the installation in the way a narrative does. So when the viewer is moving through the installation, the story is unfolding to him through the visuality of the piece, through sound, through colours.

This kind of narrative art is not very fashionable now. How did Ilya Kabakov manage to preserve the interest in such art. His installations are completely against today’s world which is moving fast, changing constantly and quickly forgetting everything. But when somebody decides to visit Kabakov’s installation he has to pay attention, go slowly, read many pages of text in order to understand it.

That’s why he creates the installation, he creates an environment in which, he thinks, he defends the feeling of time and space. He gives viewers something they have to strive for. They have a lot of time, much enough to get in a labyrinth and find a goal. You walk in a labyrinth, you walk through a strange configuration, and between you and the story there is no interference. For somebody else you are also a part of this visual element because a person moving through the labyrinth, watching the drawings, reading the texts is also a part of the world of art.

One could say Ilya Kabakov is a kind of an ancient storyteller.

Yes. Every artist is a storyteller.

Thank you very much.

Photos: Atlas Gallery, Łódź, Poland

Check the archive

nr 25 October 2006

theme of the issue:

AVANT-GARDE

< spis treści

Article

From the Editors

Interview

Avant-garde artist or a storyteller - interview with Emilia Kabakov - Artur Zaguła

Presentation

Janek Simon

Analysis

Avant-garde hard time - Artur Zaguła

Career in Culture

Souls agreement - interview with Agula i Tom Swoboda

Culture Industries

Avant-garde salary - Artur Zaguła

Workshop

To create and live - Maciej Mazerant

Young Culture

Something new - conversation with Jankiem Simonem

On the margin

Avant-garde - conversation with custodian Paweł Jarocki