Analysis

Polish design roots

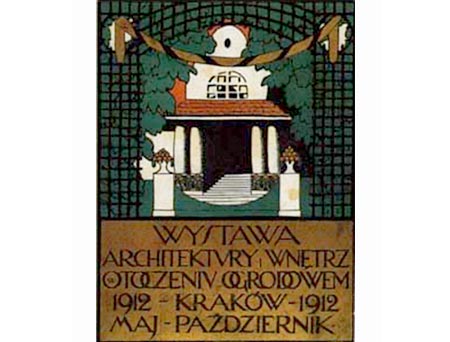

Poland won 36 Grand Prix (Zofia Stryjeñska, Henryk Kuna, Józef Czajkowski, Tadeusz Gronowski, and others), and out of 250 awards we got as many as 169. All art critics were much impressed by the Polish pavilion. Waldemar George wrote in his review of the exhibition: “…the most harmonious, the most original and consummate of all the foreign pavilions. Since it is, first of all, an excellent unity, it remains most Polish being modern, and still preserving tradition in the best meaning of the word. Its lantern of angularly cut glass, so new in its concept, full of free geometry, slickly resembles, without imitating, some strangely shaped Krakow belfries… An architect Mr Czajkowski made it a real piece of art that seems to be in 1925 what the Finnish Pavilion was in 1900”.

A poster from the Exhibition of Architecture and

Interior Design in the Garden Surrounding, Krakow 1912.

But let’s go back to the beginnings of what can be defined as Polish Design. It seems reasonable to start our deliberations from the end of the 19th century when it finally became clear that a new way of thinking about design should be developed. An era of traditional handicraft came to an end, but industrial products dissatisfied many tastes. A number of movements started to try to find new solutions to that problem, of which English Arts&Crafts Movement was the most famous. Also in Poland such attempts were made. The key character in this movement in Poland was Jerzy Warcha³owski who, following the example of John Ruskin, wanted to create a peculiarly Polish style. Warcha³owski was a co-founder and a main theoretician of the Polish Applied Art Society (1901-1913), whose members were artists such as Józef Mehoffer, Stanis³aw Witkiewicz, Stanis³aw Wyspiañski, Jan Szczepkowski, Karol Tichy, Józef Czajkowski.

Józef Czajkowski, Polish Pavilion at the International Exhibition of Decorative Art in Paris in 1925.

The Society aimed at stimulating artistic activity and involving craftsmen in the creation of applied art. Its statute read: “The Society aims at imbuing a passion for Polish applied art, facilitating its development and introducing it into industry”. The Society organized exhibitions and shows in Krakow, Warsaw and Lvov to present all fields of functional art, such as functional graphics, furniture, fabrics, paintings, interior design, monuments of wooden architecture. The final note of the Society’s activity was the Exhibition of Architecture and Interior Design in the Garden Surrounding in Krakow in 1912. It is believed to have been a watershed in the history of Polish Design and the beginning of modern thinking about interior design. Polish Applied Art, following Stanis³aw Witkiewicz’s recommendations, drew from sources such as folk art. It was supposed to enable – in combination with new tendencies – the creation of a national style in Design. However, unlike the Zakopane style, the proposals of artists gathered around the Polish Applied Art went in a somewhat different direction. Warcha³owski believed that folk patterns should be processed in a creative way. And therefore they should not be repeated straightforwardly, but confronted with an individual style of an artist, with contemporary tastes, considering the function of an object made.

Zofia Stryjenska, Encounter, from the series Passover, 1918

In 1914 a new society Krakow Workshops was founded to replace the activity of the Polish Applied Art. Besides older colleagues, younger artists appeared, such as Antoni Buszek (a painter, technologist, batik dyer), Zdzis³aw Gedliczka (paintings, kilim carpet making, illustration, weaving), Karol Homolacs (theoretician of applied art, graphic and kilim designer, furniture, illustrations), Wojczech Jastrzêbowski (painter, graphic designer, teacher, interior designer, furniture, tapestry making, illustrations), W³odzimierz Konieczny (sculptor, graphic designer, poet, theoretician), Bonawentura Lenart (graphic, lettering, artistic bookbinding, teacher), Kazimierz M³odzianowski (metal), Zygmunt Lorec (painter, graphic designer, poster, bookplate designer, kilims, toy designer, illustrator), Zofia Stryjeñska (painter, graphic designer, designed illustrations, tapestry, china patterns, toys and dolls), Karol Stryjeñski (architect, graphic and interior designer, designed furniture, kilims, toys, illustrations), Zofia Szyd³owska (ceramics). Krakow Workshops extended the ideas of their predecessors in new historical conditions after Poland regained independence. They finished its activity in 1926, after the greatest triumph of Workshop Artists, i.e. the Paris exhibition in 1925.

Zofia Stryjenska, Polish Dances, Krakowiak, 1927,

Jan Szczepkowski, the Assumption Altar, 1927

Irena Hum, a researcher of Polish design art in the first half of the 20th century wrote about the Paris triumph: ”A group of outstanding artists who showed their works at the exhibition was the closest to the programme specified in Jerzy Warcho³owski’ proclamation – they wanted to present their own form of national style synonymous with official art. Owing to the patronage of the young country and to their own will to manifest national resilience they managed to erect a unique monument to Polish art, stylistically consistent, logically constructed and in conformity with the keynote of the exhibition…The Paris triumph was also the fulfilment of Norwid’s vision of the Polish national art”. It should be however admitted that apart from artists who came from Krakow Workshops, also artists from the Rhythm group, such as Wac³aw Borowski or Henryk Kuna contributed to the success in Paris. Some, like for example Zofia Stryjeñska, belonged to both the circles. Besides, that was her who achieved the greatest individual success at the Paris show. Stryjeñska won four Grand Prix for mural paintings, a poster, a fabric and a book illustration; she was also awarded the Order of the Legion of Honour. For people in the West the artist’s immersion in Polish tradition was particularly important, as well as her knowledge of modern tendencies. Stryjeñska did not repeat French trends, but presented her own vision and style. Her paintings, illustrations and projects were the affirmation of life and nature, full of optimism, vitality, colour. Their greatest merits were decorativeness and exoticism, like say topics that drew from gipsy traditions or referred to Polish folk customs.

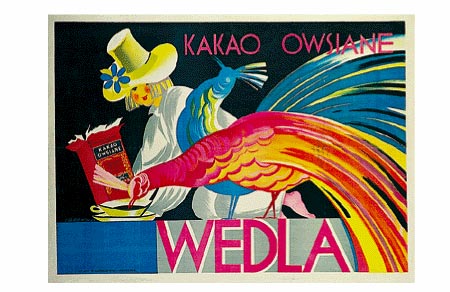

Tadeusz Gronowski, Oat Cocoa made by Wedel, 1927

The final note of the movement based on Warcho³owski’s idea was the foundation, in 1926, a Cooperative of Artist and Craftsmen “£ad” (“Order”). Its members were the youngest artists involved in interwar Polish Design. However, that group was much more pragmatic, geared mainly towards work and not theoretical deliberations. They believed it is the practice that really counts and not theoretical justifications.

Finally, I would like to say a few words about modernist movement which is a polar opposite to the one described above. I am speaking about constructivist avant-garde, represented by artists such as Henryk Sta¿ewski, W³adys³aw Strzemiñski, Maria Nicz-Borowiakowa, Mieczys³aw Szczuka, Szymon Syrkus, Aleksander Rafa³owski and Barbara and Stanis³aw Brukalski. They were inspired by the ideas of functionalism, and preferred abstract, geometrical forms. However, those who would think that functionalism is related to avant-garde only would be wrong. Let me finish with a quotation from Józef Czajkowski, a creator of the Polish Pavilion at Paris exhibition: “And here we come to believe that there is no art applied or pure, little or great, there is no adornment because it is not about decorations but about creation of a self-contained whole, and while in the past artists started from making individual objects, today a whole is the aim […]. From the inside, as from the primitive cell, the development of the house must start […], its shape and nature depending on the needs and characters of its occupants”.

Check the archive

nr 23 August 2006

theme of the issue:

EUROPEAN DESIGN

< spis treści

Article

Purpose for Europe

Presentation

European design

Analysis

Polish design roots - Artur Zaguła

Career in Culture

Brand "kikina" - interview with Elena Kikina

Culture Industries

Image design - Maciej Mazerant

Young Culture

I want to awaken the consciousness of the recipient - conversation with Lotte van Laatum

On the Margin

Design, misunderstood tool - Jose Luis Casamayor